Tl;dr:

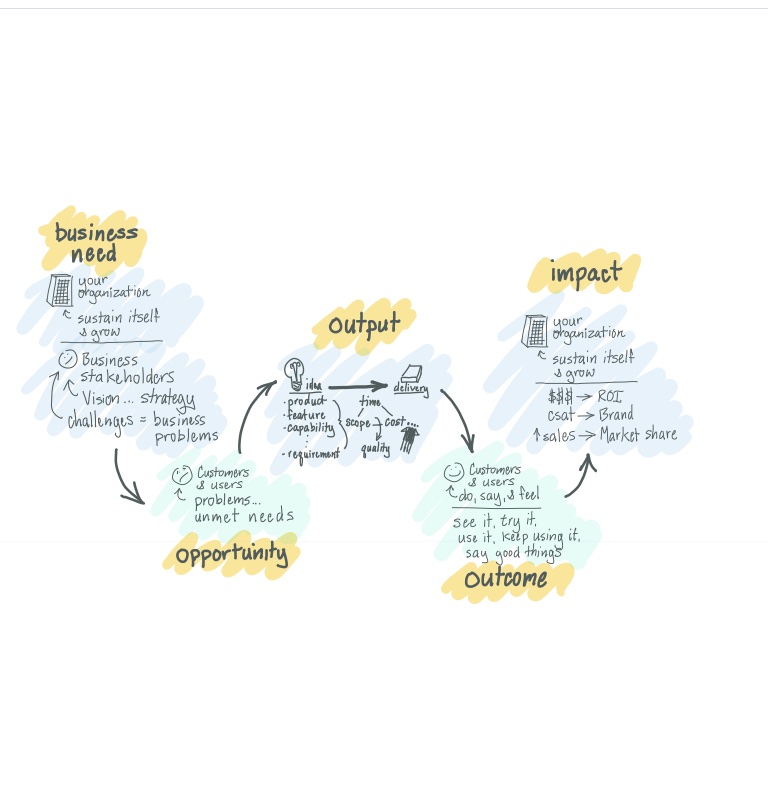

This article describes the simple language I use to describe product development: opportunity, output, outcome, and impact. But more importantly it describes the tensions and unexpected implications in the model:

- Customer problems aren’t business problems

- We can’t directly solve business problems

- On time delivery doesn’t lead to customer or business success

- Focusing on business success alone is harmful

- Focusing on customer success alone is harmful

- Aligning our purpose with our organization’s purpose is really what motivates us.

If you understand all that stuff, then, there’s no need to read the article. But, if this isn’t quite landing for you or your teams and you’ve got a spare 15 minutes and some interest, please proceed.

Feeling tension

Tension. I felt it when I finished and delivered my first project as a professional software developer in the early 1990s.

I worked for a company who built software for brick and mortar retailers. I was responsible for creating a first ever online ordering experience for one of our clients. Back then I installed the product along with its Oracle database and supporting web server on a system and delivered it to my client where I then installed it in their environment and showed them how to use the software. That’s where things went wrong.

As I showed them how to use it it became obvious that completing an order online took a long time. Much longer than just telling someone the order over the phone – which is what their customers had been doing. It wasn’t just slower, it was more complicated. More complicated because the software couldn’t give people the help that their human customer service people could. Despite that being obvious to me and the people I was working with that day, we went live with the online ordering solution with a small group of pilot customers. After that, it was obvious to everyone.

Oddly, I’d delivered on the “requirements” on time and received a hefty bonus for my effort. And, our company was paid quite a bit for getting this early online ordering experience live. This is when I first learned about the tension between product success and project success, about the tension between business success and customer success.

Product success is not project success.

Let’s start by getting clear about that.

What makes a product successful?

Think about a product you love. One that you’d happily recommend to someone else. Think about what you’d tell them. Stop for a few seconds and do this. I’ll wait.

Now let me try and read your mind. You likely thought of things like:

- “It’s easy to use”

- “It solves a problem”

- “It’s fun to use”

- “It’s a good value”

- “It saves me time”

- “It saves me money”

- “I use it every day’

Ok, I didn’t read your mind. Those are just the things we say when we like and get value out of a product. But, notice you didn’t think things like: “it was finished on time and under budget” – because those aren’t product qualities. And, really, if that’s the best thing you can say about a product, I’m pretty sure it’s not a good one.

I work with organizations who create new products and work on improving the products they already have. If you’re reading this, I suspect you work for an organization who does this. And, even if you don’t think your organization does, I’m pretty sure I can convince you that you do. (But I’ll do that in a later post.)

In product creation we turn ideas into products. If you’ve already got a product out there, often those ideas are for new features or capabilities. Think of a tech product like Spotify. It was launched in 2006. But, think of features like discovery weekly. That one was added in 2015 to improve the product. And it did.

If you’re turning ideas into products and features, you and your organization worry about how long it’ll take – the time.. They worry about what it’ll cost. Cost for tech products is usually measured in the number of people it’ll take to design and develop the product. And, the details of that product or feature, that’s the stuff we call scope. Everyone who builds this stuff knows about the time-cost-scope triangle. Everyone knows it’s the bad news triangle.

Output is the work we do to create new products and features.

The first bad news is that you’d really like to know what you can get, what you’ll pay for it, and how long it will take. But, common wisdom says you can only know two of those things.

- Fix time and cost, and the bad news is you’ll get less scope.

- Fix time and scope, and the bad news is it’ll cost more.

- Fix time, cost and scope, and the bad news is there’s actually a fourth thing: quality. Fix time, cost and scope, and quality squeezes out like toothpaste in a toothpaste tube.

Everyone in project management knows about this challenge. And it is a challenge. I’ve certainly felt it my entire professional life. But, what’s annoying is that this stuff isn’t what matters most.

What matters is what happens when things come out

Notice that what makes a product great are the things our customers and users say after they see it and try it. It’s really up to them whether your product is great, not you. This is one of the most annoying things about being product focused. You, and for the most part, everyone in your organization have little say about the product’s success.

Product success comes from what your customers and users do, say, and feel.

When we deliver a new product or improvement to that product we hope that our customers see it, try it, use it, keep using it, and say good things about it.

We call all these things outcomes, because they can only happen after things come out.

If they never see it, that’s bad. If they see it and don’t want to try it, that’s bad. If they try it and can’t figure out how to use it, that’s bad. And if they only use it once, and don’t choose to keep using it, that’s bad. And, if any of those bad things happen to them, they may choose to write a bad review, say something negative on social media, or just tell a friend to steer clear of your product. That’s a lot of bad stuff.

Of course we don’t want any of that bad stuff to happen. We want the opposite of all that to happen. What we really need for our product to be successful is for our customers to get value out of our product.

Paying attention to product outcomes is paying attention to how our customers get value from our product.

Business benefit isn’t customer and user benefit

Somewhere in all those things customers and users do we hope we’re earning some money. In traditional products we earn money when people initially buy the product – that is after they see it and choose to try it. With most tech products and services we earn money as customers continue to use it. Services like Spotify, Zoom, Slack, or Office 365 make money by charging customers monthly. Other services like Instagram or Tiktok earn money when users view advertisements while using the product. But paying you money isn’t how customers get value. The return on investment your organization earns comes from customers exchanging money, time, or attention for the value they’re getting.

Your organization earns a return on its investment in exchange for the value it provides to customers.

Your organization has a responsibility to employees and shareholders: it must sustain itself and grow. It does that with the return it gets from its investments. When customers use our products we get ROI. When lots of customers say good things about our products it helps our brand image and brand awareness. If lots of customers hear those good things and consume more of our products than our competitors’ products, it helps us build a healthy market share. I’m sure this doesn’t come as a surprise to you, but your customers don’t care about your ROI, brand awareness, or market share.

I’m going to use the word impact to describe the benefits your organization gets from those good outcomes. I’m aware that some people use the word outcome for both customer and business outcomes, but I’m not going to. Because the challenge here is the tension between these two things. Organizations often forget that to succeed, their customers and users must succeed.

Business value is not the same thing as customer value.

Business problems aren’t customer problems

I started drawing this picture with ideas. But, that’s not actually the beginning of the story. Ideally those ideas come from discovering customer problems or unmet needs. Products help customers do something they can’t easily do without them. So, the secret here is finding the things that are challenging to your customers. If you already have customers, they may be complaining about these challenges now, so just listen to them.

Not every product solves a problem. Some products exploit the needs and desires we all have. The desire to be entertained, to feel popular, or to be challenged. It’s products like games and social media that exploit those needs.

Find a customer problem or unmet need and you’ve found a product opportunity.

Your business has its own problems, problems you may be very aware of. It may not be meeting quarterly financial targets. It may have a vision, but not be reaching it. It may be losing ground to competitors. While these are indeed problems, they’re not your customer’s problems.

Business problems are not customer problems.

Here’s the real challenge for you and your business:

Your business can’t directly solve its problems. It needs customers to solve them.

Customers help your company earn more money and improve its reputation. But, growing your company isn’t what your customers want. So, to get their help, you’re going to need to discover something they want and create a product or service that can deliver it to them. Ideally one aligned with your organization’s vision and strategy.

To solve a business problem you’ll need to find a customer opportunity.

There’s lots of tension here

Let’s take a look at this whole model.

We use our organization’s vision, strategy and current challenges to find customer opportunities. We create, launch, and improve products to exploit those opportunities. Good customer outcomes come as a result of customers seeing, trying, using, and continuing to use our products. It’s those good outcomes that drive business impacts like return on investment, brand awareness, and market share.

I’m hoping you’re feeling all these points of tension in this model stacking up. But, let me enumerate them just in case you missed a few:

Business problems are not customer problems: We can’t achieve business goals without finding customer opportunities to exploit.

Output is not outcome: it doesn’t matter how efficiently we deliver our new products and services, what matters is what our customers do, say, and feel after we’ve delivered them.

Business value is not customer value: outcomes describe how our customers get value but not how our organization gets value. Customers get value when they use our products. Our organization gets value when we monetize that in some way.

Forgetting about these tensions and not managing them leads to a number of common problems.

Focusing on business success alone leads to sinister behavior

In 2016 the US Bank Wells Fargo was embroiled in a scandal where bank employees had been opening accounts without customer authorization. It turns out that having lots of open accounts for every customer creates a great deal of business value for banks. And Wells Fargo employees were both bonused for getting that value and often reprimanded when they didn’t meet targets for opening those new accounts.

It turns out that customers didn’t want or need more accounts. Having more accounts didn’t solve a customer problem or address an unmet need. So employees, pressured to meet business goals, set aside user goals and did what they felt they needed to do. The result was a lot of bad behavior and hundreds of millions in fines to Wells Fargo.

It turns out you can create business value without creating customer value – but only until you get caught.

In the 2010s Facebook found it could make a lot of money by allowing interested parties like Cambridge Analytica to harvest customer data. They’d found a way to get value to one customer by potentially hurting another. Facebook is a marketplace product where buyers and sellers come together. Operating this type of product is a challenge because you have different types of customers that get value in different ways. And, when you focus too much on your business’ value you may find that you can hurt one type of customer to benefit another. Selling data they shouldn’t have resulted in Facebook paying an “undisclosed sum” in fines. I’m pretty sure it was more than what Wells Fargo paid!

We continue to see lots of examples of organizations promoting products making impossible claims or using unscrupulous means to keep customers paying long after they’ve stopped getting value from their products.

Focusing on user success alone leads to ruinous empathy

So, it may seem like the best thing here is to keep your focus on customer problems and unmet needs. If you’re like most companies you’ve got customers complaining, asking for things. And, we’ve always heard that “the customer is always right”… right? So, if we give them what they’re asking for, that should work.

But, a characteristic of a product is that it’s a leveraged investment. Leveraged in that the cost of building it creates value for many people. When we improve a product for the benefit of one person, it often adds complexity for others that don’t need the capability you’ve added. I’m sure you’ve used products that are mired down in features you don’t need. I’m sure you’ve used products where finding the feature you do need is tough because you have to search through all those other features you don’t need.

When you improve a product for the benefit of one customer, it adds complexity for others.

What’s more, improving a product for one person takes the leverage out of that investment. More simply, your organization’s return on that investment is low or negative relative to the other leveraged investments you put into the product. Remember, the capability you add to a product will need to be supported indefinitely by your organization. And, additional improvements you add to your product will need to fit in with the complexity you’ve created in support of helping that single customer.

Finally, I suspect some of you have had the experience of building exactly what a customer asks for only to find out they don’t use that capability you’ve added anyway. When we imagine a capability in a product, we also imagine ourselves using it and getting benefit. But, we’re notoriously bad at predicting our own behavior. Like me with my weight set in the corner and that fancy new blender, I suspect you’ve got a lot of stuff laying around your home that you predicted you’d use, but don’t.

Empathizing with your customers and users is generally a good thing. But, losing sight of the purpose of your product, to help sustain your organization, can result in disastrous results for your organization and all the other customers using your product.

The purpose problem

Over a decade ago, my team and I had just finished a release for our product. We were proud. We’d done everything we’d set out to do. Our product performed well… at least we thought so. The day we went live, my team and I agreed to be there with our pilot customer – the retailer using our product. In case something went wrong – which we were sure it wouldn’t. And, for the most part it didn’t. Everything worked “as designed.” But, beware, when an engineer tells you something works “as designed” what they’re really saying is “it sucks, I know it, but that’s what the specs told me to build.” In this case, we’d decided what to build. And, standing behind people using our product we knew we’d made lots of bad choices.

Our users didn’t necessarily know we’d made bad choices. Like lots of new users, they blamed themselves for challenges they were having. They thought that with practice, they’d get better at using the product. And, we could have let it go there. But we didn’t. We went back to the office and worked hard at smoothing out the user experience, making the product easier to use, faster to use, more fun to use. We abandoned all our regular processes… no tickets, estimates, or acceptance criteria, but lots of testing. The team worked late without being asked. And it all made a difference. A big difference.

That’s what purpose looks like. Once you’ve felt it, it’s hard to let it go. I won’t.

In Dan Pink’s book Drive: the surprising truth about what motivates us, Dan points out three factors that drive motivation: Autonomy, mastery, and purpose.

Autonomy is our desire to be self-directed. Happily my team and I were given the space to make our own choices. The hardest thing about having autonomy is accepting the responsibility that it comes with. It’s difficult for leaders to empower teams when those teams place blame on others when things go wrong. It had taken me years to build trust within my organization. That trust came from me and my team consistently accepting responsibility for the outcomes of the products we built, both good and bad.

Mastery is our desire to get better at what we do. My team had that. Mastery requires motivation and effort on the part of the individual to gain it. Gaining mastery can be supported or impeded by leadership. My team prided itself on continuously learning new and better ways of doing things. Our leadership actively supported that and encouraged us to share what we were learning with other teams.

Purpose is our desire to make the world a better place. Pink describes humans as “purpose maximizers.” We seek out “transcendent purpose.” The empathy we felt for our customers and users gave us that drive to act. We knew we had the power to make our users’ lives better. And, we wanted to. That deep concern for our customers and users was also built into our organizational culture. Yes we celebrated our financial successes. But the stories we told at company parties were about the people using and loving our products.

Purpose is our desire to make the world a better place.

This probably won’t surprise you but helping a company make more money isn’t a motivating purpose. Remember earlier when I said that focusing on business success alone leads to sinister behavior? Pink says it this way:

“when the profit motive comes unhinged from the purpose motive, bad things happen.”

Daniel Pink

Keeping stakeholders happy isn’t motivating either. Staying on schedule and building high quality products is a signal of mastery, but mastery isn’t enough of a motivator alone.

We make things that people use. When we’re doing it well, those things make people’s lives better. And, when we’re doing it really well, the value we create for our customers and users results in the business impact that sustains and grows our company. It’s motivating, fulfilling work.

And, that may be the last point of tension here. Helping people is fulfilling. I always try to be kind to people. I try to contribute to charitable organizations whose mission I believe in. I’ve always heard that giving is its own reward. When I bring the same ideals to my work, I find that it can be profitable as well. That’s been a real surprise for me. So, maybe it’s not tension… just a happy surprise.

What next?

This article is part of a series that I hope in time turns into a book. A book that’s more about mindset and culture, than process. Because I believe that mindset and culture is at the root of process anyway. A good next read might be this article: The mindset that kills product thinking.